Joe Sherlock, ACSM Copywriter |

Oct.

24, 2024

This blog features only a small portion of the extensive material included in ACSM’s Autism Exercise Specialist Certificate course, developed by the multidisciplinary team at Exercise Connection.

Autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, represents a suite of conditions and symptoms that vary from individual to individual. But broadly, as defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statical Manual of Mental Illnesses and Disorders (DSM-5), ASD comprises “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts. Those diagnosed with autism must also present with “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.”

Autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, represents a suite of conditions and symptoms that vary from individual to individual. But broadly, as defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statical Manual of Mental Illnesses and Disorders (DSM-5), ASD comprises “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts. Those diagnosed with autism must also present with “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.”

However, the definition of autism has changed over time, and it is likely — if not inevitable — that it will change again. As with any definition involving human beings, the issue is nuanced and oft debated. And again, the various traits each person with autism expresses are unique to them. As special education professor Dr. Stephen Shore says, “When you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

For the purposes at hand, we’ll stick with the DSM-5’s diagnostic requirements for ASD and assume that those who meet those requirements have autism or are autistics. (Some people prefer to adopt the label “autistic” and some do not.) And when it comes to physical activity and exercise, people with autism — particularly children with autism — have unique needs. Given the growing population of those with autism — as of 2020, 1 in 36 children in the U.S. have been diagnosed with ASD — it’s critically important that exercise professionals understand and address those needs.

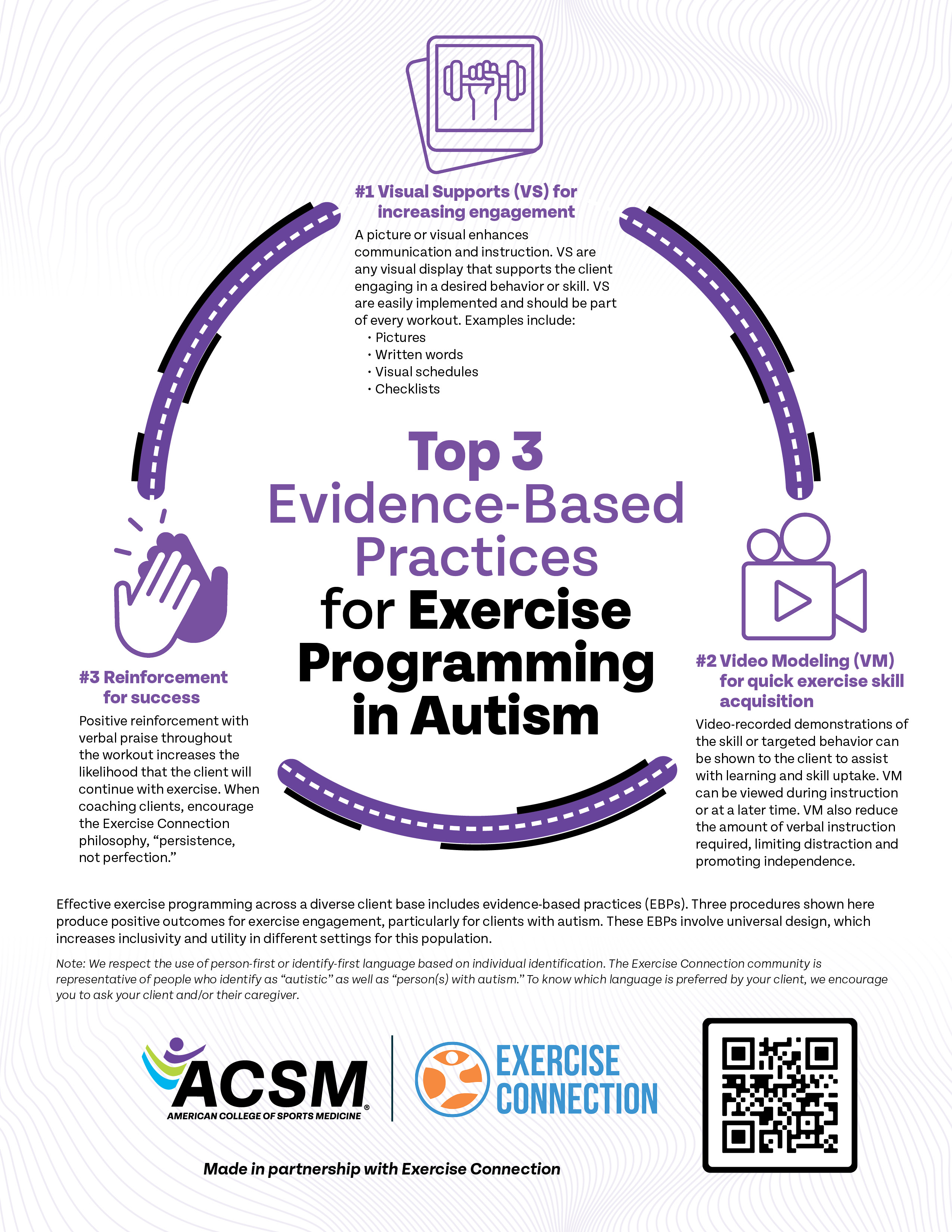

The best way to begin, then, is to understand the evidence-based practices that have positive effects on the lives of those with autism — that is, the techniques and interventions that have been scientifically shown to be effective. Past research suggests there are 28 evidence-based practices that can benefit those with autism. Each practice focuses on addressing a single skill or goal, and by implementing multiple evidence-based practices within our training modalities, we can begin to build a thorough fitness program for individuals with autism.

Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism

- Antecedent-based interventions (ABI)

- Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

- Behavioral momentum intervention (BMI)

- Cognitive behavioral/instructional strategies (CBIS)

- Differential reinforcement of alternative, incompatible or other behavior (DR)

- Direct instruction (DI)

- Discrete trial training (DTT)

- Exercise and movement (EXM)

- Extinction (EXT)

- Functional behavioral assessment (FBA)

- Functional communication training (FCT)

- Modeling (MD)

- Music-mediated intervention (MMI)

- Naturalistic intervention (NI)

| - Parent-implemented intervention (PII)

- Peer-based Instruction and intervention (PBII)

- Prompting (PP)

- Reinforcement (R)

- Response interruption/redirection (RIR)

- Self-management (SM)

- Sensory integration (SI)

- Social narratives (SN)

- Social skills training (SST)

- Task analysis (TA)

- Technology-aided instruction and intervention (TAII)

- Time delay (TD)

- Visual modeling (VM)

- Visual supports (VS)

|

These evidence-based practices have been shown to lead to improvements in a number of areas that correspond to success in physical activities, including games and team sports — from promoting communication and the ability to successfully share interests and experiences to improving motor skills and facilitating play.

These evidence-based practices have been shown to lead to improvements in a number of areas that correspond to success in physical activities, including games and team sports — from promoting communication and the ability to successfully share interests and experiences to improving motor skills and facilitating play.

In particular, positive motor-specific outcomes are linked to augmentative and alternative communication; differential reinforcement of alternative, incompatible or other behavior; exercise and movement; modeling; music-mediated intervention; naturalistic intervention; parent-implemented; prompting; reinforcement; response interruption/redirection; sensory integration; task analysis; technology-aided instruction and intervention; time delay; video modeling; and visual supports.

The experienced exercise professional will already see a number of interesting opportunities for exercise prescription and augmentation in that list.

These practices are often used alongside one another. One example might be combining video modeling and music-mediated intervention: showing your client a yoga or other stretching-based video whose positional changes are set to music and then, after the appropriate amount of practice and training, assisting your client as they follow along in real time.

If you’re interested in learning more about training those with autism, consider taking ACSM’s Autism Exercise Specialist Certificate Course, which includes not only an explanation of the evidence-based practices listed above but a thorough and in-depth look at the current state of research and practice related to autism and exercise.

Become an Autism Exercise Specialist Today